The nation remains in a state of perma-crisis with pressure and stress. In the 2022 Workplace Health Report, around a third of people reported moderate to high stress. The Mental Health Foundation says 74 per cent of adults felt overwhelmed and unable to cope in the last year. This situation is acute across all sectors and – arguably – is driving resulting personal crises in our staff. In some cases, this raises existential questions for leaders about whether it is even possible to lead healthily under these conditions. What might our leadership response be?

In a recent Harvard Business Review David Rock considered the concept of ‘quiet quitting’ stating that “…in the face of persistent and inescapable stressors people often respond by giving up. When nothing is in your control, why even try?”

The challenges we all face

Energy prices, inflation, government instability, staff shortages, bleak forward projections, supply chain budget restriction declining in real terms, and staff demanding more pay. All of this is attached to the tail of Covid, which is far from finished in terms of staff absence and employee social conditions combined with emerging new ways of working- that mostly….well…er don’t work.

The elements that compound distress are far from exclusively the conditions within corporations- also significant are the inescapable externalities in life outside which layer on the pressure and which have become harder to leave at the office threshold. The space between work and home finally evaporated in Covid.

Personal meets the professional

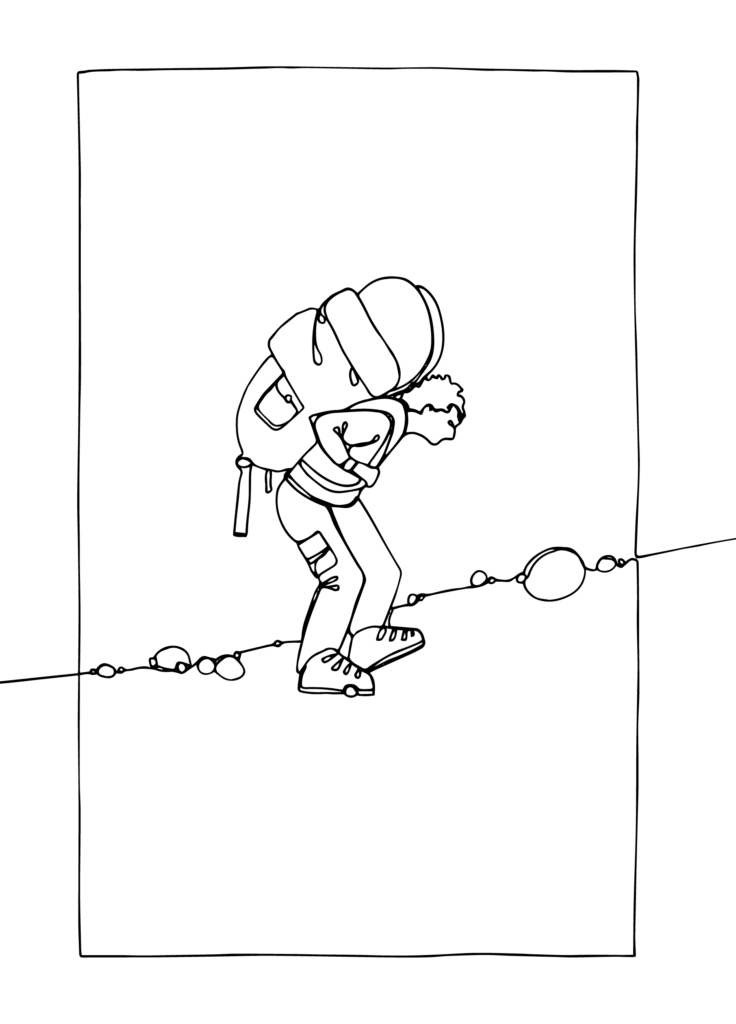

Last year, whilst in post as a CEO I underwent a period of extensive and chronic distress. This time taught me so much. My leading expertise in distress and positive coping strategies includes coaching practice, cognitive reframing, daily meditation, stoicism, support of friends and family and my Buddhist faith, which all helped, but were, frankly, insufficient. I was, as author Ruby Wax would put it, ‘frazzled’. When pressure stays high, with little time to rest, there is insufficient space in “the stress bucket”, as expressed by Babington, to respond to temporary crisis and the perma-crisis many of us experience.

My dad who passed away just over a year ago, held simple, yet endless, wisdom; always asking how work was and my reply was “I’ve got a busy couple of months and then it should ease”. He once told me that I had been saying this for over ten years.

Leading in a state of hopelessness?

Looking forward, there is little evidence that the current perma-crisis is likely to ease in its reach or longevity. It begs the question: are we now leading in a state of hopelessness? If you spoke to my former team, they’d tell you that I have (cruelly) banned the word ‘hope’ for many years; feeling that it is a refuge or pre-empting failure – it is passive and without strategy or tactics to influence outcomes. But there is a question as to whether we should even hold out for hope at all. In The Hope Circuit, positive psychologist Martin Seligman argues that “Whether or not we have hope depends on two dimensions of our explanatory style; pervasiveness and permeance”.

The literature also points to two types of pressure; challenge pressure and hinderance pressure – the latter of which we can no longer proactively remove as easily as we once could. Leaders may make best efforts, but there is a negative psychological and mental impact of constantly not being good enough. A challenge in leadership roles is the acceptance we are making suboptimal decisions daily. It is the constant selection of the ‘least-worst’ option. None of us wish to do this. There is a widening gap in discussions with staff I’ve noticed between agreeing what we should do and what we can or will do.

Worth consideration is that perma-crisis really means permanent distress, permanent fatigue, permanently working with teams and staff under high pressure, but still needing results. I feel this is new territory in extremis.

I do worry about people stepping into leadership posts and whether new senior leaders are equipped with the right, or enough, skills. I have been a practising coach for over 15 years and was a CEO for almost a decade. My skills and behaviours around coping with distress are both refined and experienced, but I remain vulnerable and am beginning to question the long-term health toll for people in senior roles. We need to find ways to support leaders, coaching can be a method to help grow self-awareness and provide practical strategies to address issues.

We must try harder to remove pressure or people will conclude that they must remove themselves– there is limited satisfaction in any job where it’s impossible to do a ‘good job’. I wonder how many people in your teams are considering this right now.

Organisational culture

Like many leaders, my biggest mental weakness is that I carry the mood of others. Businesses don’t just have cultures, I think they hold an emotional resonance, a consciousness, a mood of their own. You can feel it in corridors and meetings. When I was a CEO when the organisation was happy and calm, then I was happy. When the business felt in a place of distress, then I followed. It flows from a place of care and whilst illogical, it is true to me and many others I speak to.

There is a distinct difference between distress, pressure and burnout. To what extent are many leaders drifting between these categories and with what frequency? My hypothesis is that many leaders are experiencing physical and cognitive distortions that come with high stress and burnout symptoms more frequently. We are now more used to operating with neurobiological states of alertness. We may not be aware what our real stress levels are at all. I am leading some research on this now.

Hope and solutions

But if I temporarily permit the use of the word ‘hope’, then what hope might we hold? Anxiety happens, according to a therapist I once worked with, when our perception of our personal capacity to cope is outweighed by our perception of the situation. We can use the stoic principles of acceptance to understand our locus of control, focus our attention on shaping what we can change and illicit small victories daily in colleges. We can marshal an urgent sense of belonging whilst understanding we really cannot change much of what is now happening in our world.

We can better utilise concepts of rest and recuperation, perhaps creating proactive downtime within the day or week or holidays. This might help relieve some of the physical symptoms of working under distress and chronic tiredness I witness. We can restrict our access to the negative news cycles in the outside world. This creates a sense of helplessness and at times – more frequently – anger; ‘doomscrolling’ has been proven to have a significant negative psycho-physiological response.

All leaders expect it to be hard. Really hard. But it must be possible without compromising our mental and physical health. In a perma-crisis, the reality of distress is with us and must be proactively addressed on individual, institutional and sector levels. We cannot solve this completely, but the best we might attain is the creation of a much better and happier balance.

Dad always said that the key to success was ensuring we took steps to “get on and stay on an even keel”. Despite him never leading a team, it remains the best leadership advice I know, fitting for our times and providing the opportunity to rebalance and perhaps lead in hope.

So what first steps might you take? Who is the coach that can help you on your journey? What skills and behaviours should you urgently practice to help yourself and in turn help others?